Want to keep up with Aixle's writing? Sign up to get Sticky Notes delivered to your inbox.

When I ask people what they think about when they hear the words “community organizing,” I often hear about community-based organizations doing advocacy work. I hear about using specific strategies to achieve a “win” on an issue.

But the way I see it, community organizing is about so much more than achieving a win. It’s a mindset – a way of seeing the world. More importantly, it is a set of principles that we can use to totally rebuild and transform our schools into community schools.

Through work at Organizing for America, Leadership for Educational Equity, and the Industrial Areas Foundation, I started off in community schools as an organizer. But it was only after I took a job as chief of staff of a board education office in the Los Angeles Unified School District, that I started to truly understand what community organizing can DO to engage and galvanize a collective vision.

In the beginning, our office’s interactions with our constituents were mostly transactional: we helped them with issues they called about, and they agreed to let us contact them about events our office was hosting. The way we saw it, our value to our constituents was only as good as we were at fixing their problems.

By our second year in office, we received training on how to be better and more proactive allies. It showed us new ways of approaching relationships, and helped us learn that our work wasn’t actually to solve our constituents’ problems for them. Rather, given that students and their families faced their own unique realities every day (and we did not), what they really needed was for us to listen, work with them, and find collaborative ways to offer support.

We started hosting Family Problem Solving Groups, and worked alongside local families through a process where they identified problems in their school communities, did their own root cause analyses of the problem, unpacked relevant data, and developed their own solutions with clear action steps.

The result? Our constituents started to see us as partners who could provide the space, authority, and approach to solve their own problems. And more importantly, it worked. When those families presented their solutions to the superintendent and other district leaders, the follow up was swift. District divisions began to immediately work with the parents to help them implement their proposed solutions. They even got invited to other district committees and task forces to support other workstreams.

The experiences gave all of us – our office, the families, and even system leaders – a whole new way of thinking, dreaming, and working together.

And, it gave me an invaluable lesson: As school or district leaders, it’s not your job to “empower” your constituents – they already possess their power. Your role is about creating a culture for partnership, holding intentional collaborative space, and sometimes, providing tools to tap into the power they already have.

How can you do that? Here are a few ways you can apply some foundational principles of community organizing into your community schools work.

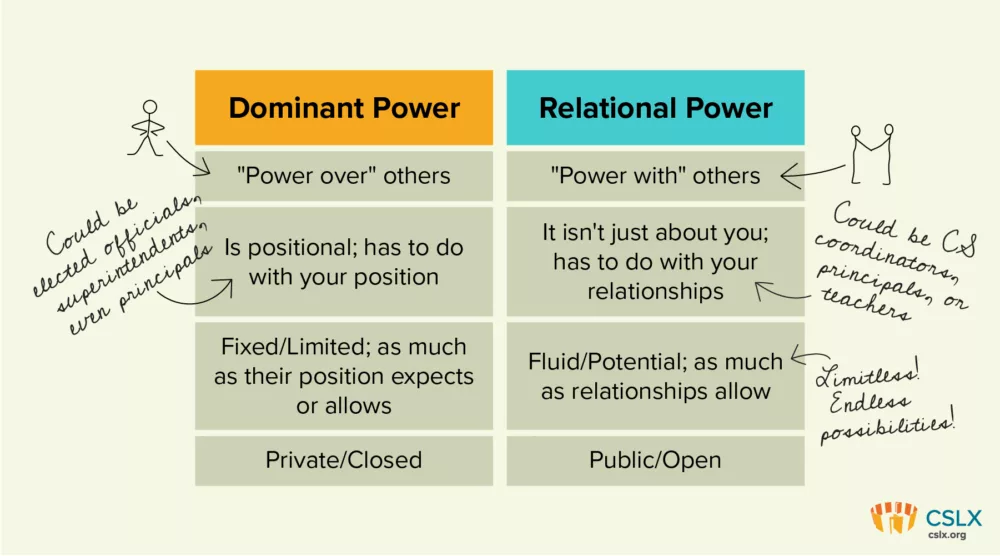

Adopting a community organizing mindset means constantly weighing the tension between dominant, or positional power and community, or relational power – “power over” versus “power with.” If you are a formal leader within a system – whether you work in a board office or at the district level like I did, or you are a site administrator or any member of school-site staff – then you hold dominant/positional power. Power in this case is fixed and cannot grow – the more power you have, the less others do. Dominant power is private and closed off from the public, so it’s inaccessible.

But even more powerful than an elected official or board office are the longstanding relationships and lived experiences of your constituents or community – their community/relational power. Why? Because this type of power is fluid and can grow. It’s totally based on the relationships you build with others. It’s open and accessible to the public.

Our internal work as an office was to recognize that in order for our community to work with us, we needed to listen with intent and humility, to acknowledge and repair harm, to collectively imagine possibility, and to share responsibility and accountability to realize our goals. And to do that work, we needed to rebuild mutual trust while recognizing that we needed each other, if we were to truly center student success.

Building trust is a fundamental principle of effective community organizing – the very same thing that is so powerful about community schools work. Trusting relationships, an enabling condition of community school transformation, must be something that you are mutually committed to. Let’s be honest – everyone has their own agenda. The magic lies in how we strategically navigate that reality and also the tension between self-interests and shared interests.

It’s common to have negative associations with the concept of self-interest. But self-interest is neutral – all of us have it. It lies in between selfishness and selflessness and literally means self among others. Understanding your community members’ self-interest means learning what drives them, what they care deeply about, and what will move them to engage and take action. In schools, the power of this tension is that by balancing and leveraging your self-interest against your commitment to the larger school community, you can determine the shared interests that will motivate students and families to be more engaged in their schools.

Ultimately, when you put community organizing principles and community school essentials together, you get a school that holds trusting relationships at its heart, even (and especially) when it’s uncomfortable.

There is so much power in intentionally and strategically navigating how we engage others, how we navigate power, and how we move past personal agendas and toward shared interests.

So, if you’re a community school coordinator, principal, or other member of school site staff, consider the type of power you hold. Pay attention to who is at your table, and whose voices may be missing. Consider the agenda you’re pushing and whether it represents the interests of your community – and I mean your entire community. Not those of only a select few.

And if you’re looking for tools, check out Maria Avila’s “Building Collective Leadership for Culture Change”. It’s a fantastic resource for understanding how to use community organizing to create more collaborative cultures in your school or district – and I’m not just saying that because I co-authored a chapter in the book. ;)

Aixle

Aixle is Director of Learning Partnerships at CSLX. She is a practitioner, former educator, community organizer, and policy advocate with a focus on intentional, collaborative partnerships to support youth, communities, and systems. Get in touch with Aixle via email at aixle@cslx.org.