CS Journeys: Garden Grove builds a foundation for growing their community schools vision

Mar 12, 2025

Welcome to Community Schools Journeys! In this series, practitioners like you share how they bring various aspects of community schools implementation essentials to life in their unique school communities. Want to explore what a Journey could look like for your context? Get in touch.

Introduction

Founded in 1965, Garden Grove Unified School District (GGUSD)

is the third-largest K-12 school district located in Orange County, California. Enrolling close to 40,000 students, GGUSD serves families from Garden Grove, and neighboring portions of Anaheim, Cypress, Fountain Valley, Santa Ana, Stanton, and Westminster. GGUSD has been awarded a number of honors including being named a 2018 California Exemplary District, a California Honor Roll District, and numerous California Distinguished Schools. Home to three AVID (Advancement

Via Individual Determination) Demonstration Schools, the district was also awarded the 2021 Best Communities for Music Education Award from the National Association of Music Merchants (NAMM) Foundation.

GGUSD is guided by the Garden Grove Way, a strategic plan launched in 2013 by the GGUSD Board of Education, long-serving superintendent Dr. Gabriela Mafi, and co-created by interest holders across the district. The plan was collaboratively developed by students, families, and staff, and guides everything that happens in GGUSD, from large-scale budgetary and programmatic decisions to site-level academic and school climate-related goals. The Garden Grove Way has three priority areas: 1) Academic Skills, 2) Personal Skills, and 3) Lifelong Success – all of which come together to enact the GGUSD vision of preparing all students to be successful and responsible citizens who contribute and thrive in a diverse society.

Having recently been awarded close to $12 million as part of a state grant program to implement the community school strategy (the California Community Schools

Partnership Program, or CCSPP), GGUSD focused first on ensuring a strong foundation for

implementation. This Community Schools Journey draws on conversations with district-level

leaders in the GGUSD community to learn how they went about planning and building the

foundation for their community schools vision.

The community schools structure

The importance of planning in community schools development

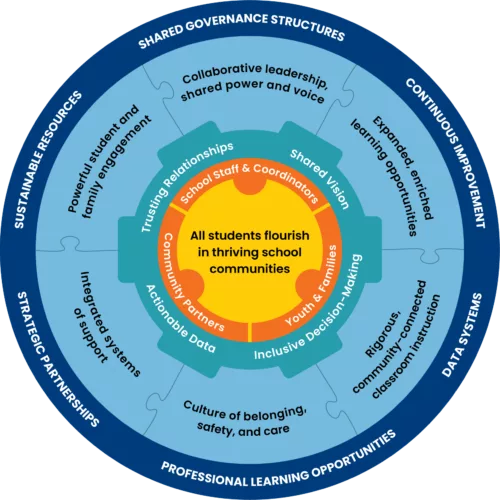

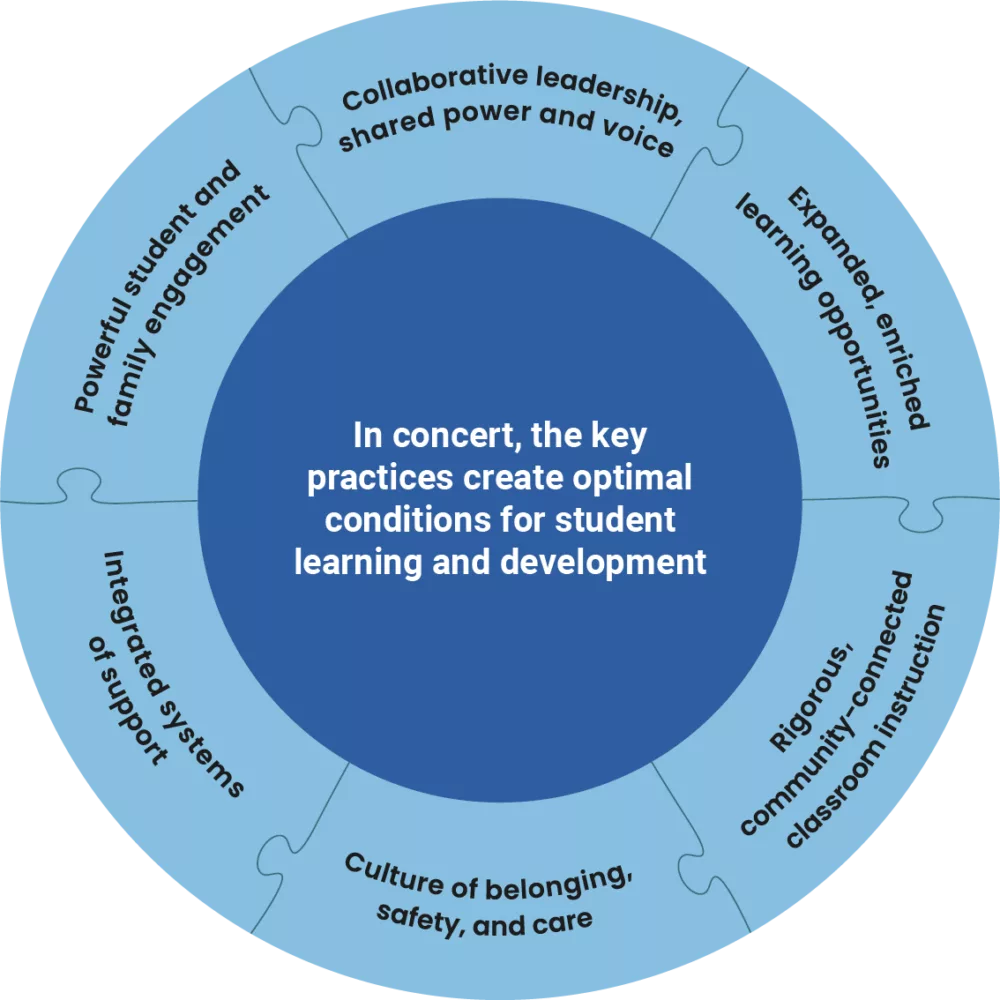

The Essentials for Community School Transformation (from now on referred to as the Essentials Framework, Community Schools Forward, 2023) provides a robust implementation framework to understand the dimensions that are integral to an effective community school strategy. Each of the key practices in the Framework are core components of a successful community school. Collectively, they contribute to a strong, interconnected system that supports whole-child learning and development for all young people. But meaningful development, implementation, and integration of these practices does not happen by accident.

Like any attempt at system-wide transformation, the community schools strategy demands significant leadership, time, and resources dedicated to planning and development. Put simply, community schools are not built in a day. While extensive planning time has not always been possible in every school community, the California Community Schools Partnership Program (CCSPP), launched in 2021, encouraged schools and districts who were interested in adopting the community schools strategy to undertake a comprehensive planning process prior to submitting an application for implementation grant funding. This focus on building a strong foundation has allowed many LEAs and schools across California to build their work systematically instead of “building the car while driving it.”

Through CCSPP Planning Grants – California’s unique funding opportunity to support inclusive planning across two years – districts without existing community schools would be able to learn more about the community school strategy, deepen relationships with key interest holders (e.g., students, families, educators, and community partners), and collaboratively develop a shared understanding and vision for what their community schools could be.

GGUSD was awarded a Planning Grant in the first round of CCSPP funding (2021) and initially proposed three focus areas: 1) integrated student supports for learning, social and emotional development, 2) school-based health and wellness, and 3) family support and community resource navigation. These areas built upon the district’s prior successes and aligned resources and supports that served eight school communities across two high school feeder patterns. The schools in these particular feeder patterns are distinct from the larger Garden Grove district in that they serve higher populations of English language learners and students eligible for the federal Free and Reduced Lunch Program.

More importantly, each of the eight school communities has a rich and celebrated history of joy, resilience, and possibility despite the systemic challenges that they have faced. Through interviews with school and district staff, focus groups with families, and student empathy activities, it quickly became apparent that these school communities were willing to leverage their unique strengths and assets to ensure that their students thrive.

Planning to plan: The Garden Grove Way

A community school strategy is sometimes touted as a vehicle for transforming public schools. Transformation, however, is not just a technical challenge to be addressed by new programs, initiatives, or partnerships. Foundationally, community schools leaders and interest holders recognize that without attending to the enabling conditions for success, any change effort will fail or peter out. The four enabling conditions include: trusting relationships, shared vision, inclusive decision-making, and actionable data. While keeping the priorities of the Garden Grove Way (Academic Skills, Personal Skills, and Lifelong Success) at the forefront, GGUSD’s planning journey gives practical insight into how these conditions were cultivated and strengthened throughout the community schools planning process.

“Each school community contains unique assets and resources, specific needs, vision, and goals. For effective implementation, these are assessed and addressed through trusting relationships, shared accountability, and differentiated responsibility. Community school planning begins by convening youth, families, educators, and community partners to shape the future of their school and strengthen their community."

Community Schools Forward, 2023

Staff and school personnel support for the strategy began with a culture of deep trust in district leadership. District leadership, including the superintendent, assistant superintendents for K-12 instruction, and program directors, prioritized a clear and shared understanding of the community school strategy and what it meant for specific schools and roles. They started with district-level leaders and subsequently expanded to site-level design teams.

Representatives from families, teachers, community partners, and classified staff were part of the site-level design teams as GGUSD leadership wanted the insights and voices of all those connected to the school system at various levels to be meaningfully included. District leads, including Luisa Rogers and Anabel Pauline, respectively, the Program Director and Teacher on Special Assignment (TOSA) tasked with leading this work, also reviewed initial data (e.g., GGUSD strategic plan surveys, interviews with school-based staff, and family focus groups) to better understand what further data needed to be gathered to craft a shared vision of how the community school strategy might unfold in Garden Grove.

Shared vision

After receiving a CCSPP Planning Grant, senior district leadership had clear hopes and dreams of what a community school strategy could look like in Garden Grove and how to develop this vision with their school sites. One of the initial steps was to ensure that those involved in the project had a shared understanding of what the community school strategy is, what it is not, and what it would take to support schools to successfully implement the strategy.

Importantly, the district leaders most responsible for the planning process were long standing members of the GGUSD community. They had decades of experience in supporting the district and its schools across numerous initiatives and reforms, and insights into where the district had already been and what some initial priorities might be.

Oftentimes, educators, parents and students are rightfully weary of new initiatives and efforts at school reform — “initiative fatigue”. To be successful, GGUSD leaders had to ensure that everyone understood that this wasn’t a new initiative, but as Anabel Pauline, the Teacher

on Special Assignment for Community Schools explained, “all the different pieces to this community school wheel and puzzle are... the functioning of how we [at GGUSD] do school.”

This process of building a shared understanding included hosting multiple internal workshops and meetings with senior district leaders and site-level design teams to foster alignment across the first eight school sites. However, building a shared vision didn’t stop with a couple of training sessions and meetings. It was an iterative process that continually shaped the district’s strategy and action steps. Process provided a strong foundation in building a truly shared vision by including the perspectives and voices of site principals and other interest holders through formal and informal conversations and through an initial assets and needs assessment.

Assets and Needs Assessment

By drawing upon GGUSD’s strategic planning and leadership expertise, the district’s assets and needs assessment elevated questions like “What do we want to know more about?” and “Who do we want to hear from?” Using a “street data” approach (Safir & Dugan, 2021; see Table 1), these questions help school staff to learn more from their communities in a systematic and structured way.

With support from CSLX, district staff and GGUSD’s eight site principals worked towards getting school staff and student perspectives through a variety of data collection and analysis methods. In order to facilitate a process that allowed site-level design teams (consisting of administrators, teachers, classified staff, and parents) to work together on analyzing and understanding the data, district leadership provided invaluable substitute coverage for each of the schools for two full release days so that staff could have focused planning time. These release days – which allowed for full participation of school and district leadership, along with teachers, classified staff, and families – were designed to incorporate new insights into the planning process.

For example, to better understand students’ experiences and perspectives, Anabel worked with principals to design a student empathy activity (e.g., empathy interviews, shadow a student for a day). The district also worked with principals to map community partners at each school site and consider which community partners could help with data collection (e.g., enrollment rosters, engagement activities). Each site team used their second release day to make sense of their findings and update their site-level community school visions. District leadership also refined their understanding of how each site-level plan rolled up into a cohesive district-wide strategy.

Lesson learned

Building a shared vision requires a shift in mindset. Oftentimes in schools, developing

a “shared vision” is a top-down approach. While there may be listening sessions or focus groups or surveys seeking “input,” the critical work of collaborating on what all interest holders want in their schools is often rushed due to a lack of time and resources. However, the community school strategy demands a shift in this practice by ensuring that all interest holders understand the work that needs to be done and have the space and time to hold the conversations necessary to transform the typical way that we “do school.” Most importantly, to establish a shared vision, initial ideas (whether grassroots-driven or offered by senior leaders) must be consistently revisited with an ever-growing collection of voices and insights until there is a clear, full, and inclusive picture of where the school community would like to go.

An iterative process is not easy, and can sometimes be seen as inefficient. It can be especially challenging in the early days of planning when there is often a desire for a rulebook or template that dictates where to go and how to get there. As Lorena Sanchez, Assistant Superintendent for K-12 services, explained, “dealing with hypotheticals and people [including herself] who want to be perfect from the very beginning...[while] not understanding that the process is what gets you there.” Through trial and error, along with a willingness to learn and grow, the district began to fully understand how important it was to let a shared visioning process play itself out. Engaging in this thoughtful process was also imperative to establishing the enabling condition of trusting relationships.

Trusting relationships

Though not meant to be seen as “just one more thing”, community schools can require fundamental shifts in how people understand what it means to “do school.” Garden Grove’s long-standing reputation as a strong, well-performing district has led to widespread trust in the district’s senior leadership from teachers, site administrators, and families. Practically speaking, this also means that very little in the district happens without taking the time to gather the insights, contributions, and formal support from leadership. Although this reality may mean that district-level decision-making around change happens slowly, there is also a strong sense of solidarity and commitment across the district, including teachers, school leaders, and classified staff. Deepening trusting relationships that already existed (such as those among the senior leadership team), and building new ones (e.g., more intentionally including community partners and classified staff in planning), came through multiple avenues in the community schools planning process. One profound opportunity to build trust was through initial conversations with interest holders through the assets and needs assessment process. By viewing the assets and needs assessment as a process for school visioning and relationship building, rather than a compliance-oriented checklist, Anabel Pauline was able to leverage existing relationships within the district to build the foundation for new ones.

Building trusting relationships happens more easily when people really get to know one another, their values, and their motivations. One way this unfolded in GGUSD was through intentional exercises and workshops that incorporated personal stories, experiences, and team-building. For example, Luisa Rogers, the Program Director overseeing the community schools planning processes explained:

Of course, yes, trusting relationships are important, but you literally had to break down barriers to be able to get to a point where people are really speaking from the heart. And they’re not afraid to share what they’re feeling or whatever their belief is, because of fear of, you know, being judged, if you will. So...it’s like taking it to another level.

Luisa Rogers

Site design teams used the information from these experiences to talk about their ideal visions of environments for students, families, and educators. As conversations expanded from the internal district team to the site-level design teams, the influence and importance of trusting relationships became even clearer. For example, Lorena shared:

Well, for me, I had the opportunity to sit with teachers and parents, students and former students. So it was really nice for me to hear their perspectives to know that we can count on them. I never had any doubts, but it never never hurts to hear it again; that they want to work with us... So it really just lends itself to strengthening our circles of not just networking, but building relationships [with] everybody who was a stakeholder and came together. I feel like that was the most valuable piece for me. Obviously, the [quantitative student outcomes] data is important. And obviously, the whole mission and vision and the purpose for us getting together is our number one, but it was just icing on the cake to make connection[s] with the staff and the parents and to have this vehicle [the community schools planning process] to do it in.

Lorena Sanchez

The connection and trust among principals, staff, students, parents and community members is essential to create transformative change. Leaders valued these spaces to strengthen relationships and held them at the forefront as they continued implementing their community school strategy.

Lesson learned

Focusing on “street data” influenced how GGUSD strengthened trusting relationships.

Leaders and partners created spaces where people (especially those who did not always have opportunities to regularly and meaningfully interact, like families and classified staff (e.g., family liaisons and front office workers)) connected on a human level to make the other enabling conditions possible. There was a need to address and break down barriers to get to the point where people could be vulnerable and speak more freely about their hopes for their school and community.

Actionable data and inclusive decision-making

Actionable data affects all the other enabling conditions as it is integral to how shared visions are created, trusting relationships are built, and inclusive decisions are made. The GGUSD journey highlights the importance of expanding how leaders think about data. Luisa explained that “of course the district has data, but the data now included focus groups, interviewing students, empathy interviews”, which are often different from the more quantitative forms of data (e.g., student achievement results, large scale administrative data) that many districts are used to relying on.

Similarly, site design teams were able to rethink the ways that they approached data analysis. Luisa explained that looking at data in this way was a direct result of their community school journey. She described how with this shift in thinking, it is impossible to go back to the “old way of doing things.” GGUSD’s strategic data and assessment data were important tools that gave some insight, but adding in other types of data brought a deeper understanding of how students are doing. Ultimately, speaking to such a wide range of interest holders as part of the planning process helped to foster inclusive decision-making.

In Garden Grove, inclusive decision-making was the other side of the actionable data coin. Having data to support conversations with diverse interest holders is central to most of the district’s crucial decisions, like funding priorities, program offerings, and cultivating external partnerships. But shared decision-making isn’t just a matter of having the right information and the right people; there needs to be a shift in who makes decisions and how those decisions are made. For example, GGUSD has strong centralized leadership that is generally trusted to make decisions that affect schools, students, staff, and families. This means decisions from ‘top brass” are usually well-received by district and school staff and the community, and the subsequent support from senior leadership is clear and consistent, further helping to mitigate confusion at the site level.

A community school strategy, however, isn’t always about following the lead of the grass tops, even if top-down leadership and decisions are in sync with the perspectives and priorities of students, families and staff. Authentic inclusive decision-making necessitates engaging as many voices as possible, as it’s not just about the ultimate decision, but the process in getting there. Throughout the design phase, bringing in the voices of interest holders was part of the needs and assets assessment, planning meetings, and listening sessions, but most importantly these perspectives all influenced the priorities and action steps for the district and each of its community schools.

From the beginning, district leaders wanted principals to build upon the strengths and areas of growth in their schools, and to iteratively engage their communities throughout their planning and implementation. As sites worked on their needs and assets assessment, principals led discussions with staff and design teams using the information from interviews, focus groups, and surveys to update site-level priorities. Principals and their site teams also brainstormed ideas for how they wanted to move forward in those priority areas. District leaders, including assistant superintendents and program directors, acted as thought partners, offering suggestions on how the perspectives of their community informed the Garden Grove Way.

The community school idea of inclusive decision-making called to go deeper than existing structures to truly involve more voices. Luisa explained:

The work that we were doing with this group of people, it was everyone at the table. There were parents at the table. There were classified staff members. There were teachers, administrators, district folks. We were all there together and there wasn’t a hierarchy... But everybody’s voice counted, everybody’s thoughts got jotted down. [What] were we going to do? How are we going to find out what we need? What should we do? How are we going to go about it? So it was more than just rubber stamping something; it was developing something together, and then going out and finding out and researching it, and bringing it back to the whole, which was a different process than what we traditionally do.

Luisa Rodgers

Lesson learned

Bring as many people along with you as early in the process as possible. This is one of the most challenging aspects of the community school strategy for school systems, but it is the cornerstone of being a true community school. All interest holder voices are valuable and should be what shapes a thriving school community.

What can practitioners learn from GGUSD’s community school journey?

Start with what you have

A community school strategy doesn’t start with a new checklist of activities and assessments. It is important that planning builds from the assets (and data) that you already have. Along with building a shared understanding of what the community school strategy is, GGUSD’s initial planning meetings focused on the district’s how, specifically the process that would be necessary for meaningful school transformation. Senior district leadership started with data from their annual strategic plan survey to set initial priorities for consideration. These data provided insight into staff perspectives on their personal skills and goals and how students were reporting progress on their scholarly habits, social emotional well-being, climate and culture.

Take your time

The CCSPP Planning Grant provided up to two years to work with as many members of the school community as possible to envision what the community school strategy could look like at each school. This opportunity provided schools with an invaluable resource, which is a rare feature of competitive grant programs—time! Rather than rush through a process that is inauthentic and leaves out the voices of harder-to-reach community members, community school leaders should commit to having protected time to learn from and work with all interest holders. This is the time to reflect on the past, talk about the present, and share dreams for the future of the school community. It will not be perfect the first time. You will repeat conversations or conduct new interviews or re-launch surveys to learn more about your community’s inherent strengths and challenges. However, that time spent together working is an invaluable asset in collectively building and working together towards a shared vision.

What can policymakers learn from GGUSD’s community school journey?

In a May 2022 EdSource article, Linda Darling-Hammond, State Board of Education President, described the ways in which schools themselves must change, and how teachers and principals might rethink their roles and relationships. In that same article Milbrey McLaughlin, a professor emeritus of education and public policy at Stanford University expressed her concerns about whether administrators and teachers would fundamentally change how they operate schools, and connect to parents and their communities.

Change, however, does not happen because of a grant program alone. GGUSD’s journey highlights some important considerations for policymakers and advocates to support successful planning processes for LEAs.

- Fund Planning Grants for LEAs. The CCSPP describes community schools as an equity- enhancing strategy that aligns with and can help coordinate and extend initiatives at

the school, district, county and state levels. Alignment and coordination take substantial time and resources, especially to meaningfully include students, teachers, families, and community partners. - Simplify expectations and provide planning guidance that prioritizes the development

of enabling conditions. The partnerships and planning activities section of the

CCSPP Planning Grant questionnaire included questions around: student and family engagement; meaningful involvement of all interest holders to identify assets and needs; shared decision-making around vision, goals and priorities, supports and services;

and continuous improvement. These aspects – while foundational to community

schools – are not simple and easy. The enabling mindsets, structures and practices of these “planning activities” require explicit attention and can take two years or more to develop. By strengthening the enabling conditions for success, it is more likely that other programmatic components – like services and partnerships – are more responsive to the priorities shared by the entire school community. - Develop and share practices that support long-term thinking, continuous improvement,

and partnership creation and collaboration. Many practitioners get stuck in the

technical mechanics of the initial “steps” of community schools development. Instead of developing “muscle memory” for inclusive decision-making, meaningful reflection, and continuous improvement practices, decision-makers are quick to demonstrate impact by citing “satellite data”-focused changes. However, the reliance on compliance instead of transformation misses the point. Sustaining community school practices for long term, transformative change must realistically account for the comfort and allure of the status quo to “just get things done”.

Questions for consideration

- What’s the current state of your district or school’s relationship with families?

With community partners? What have these relationships been like historically? - Is there a shared understanding of the community school strategy across your LEA leadership team? Across your district? Across school sites? Across interest holders?

- Who is currently involved in developing a vision for your district and schools? Who do you need to add to the mix?

- What data do you already have access to? What’s your starting point, and where are the gaps in knowledge that you need to fill? What’s your plan for filling those gaps?

- Do your district’s strategic plan and LCAP reflect the voices and priorities of a wide range of interest holders? Who might you work with to set out a plan for planning? What would your ideal planning timeline look like?

- Do existing school transformation efforts in your district align with each other (e.g., expanded learning, english language supports, mental health services)? What about school-level student-facing initiatives? How might you start to bring those pieces together?