CSLX Remarks at the White House

CSLX•Mar 28, 2022

CSLX•Mar 28, 2022

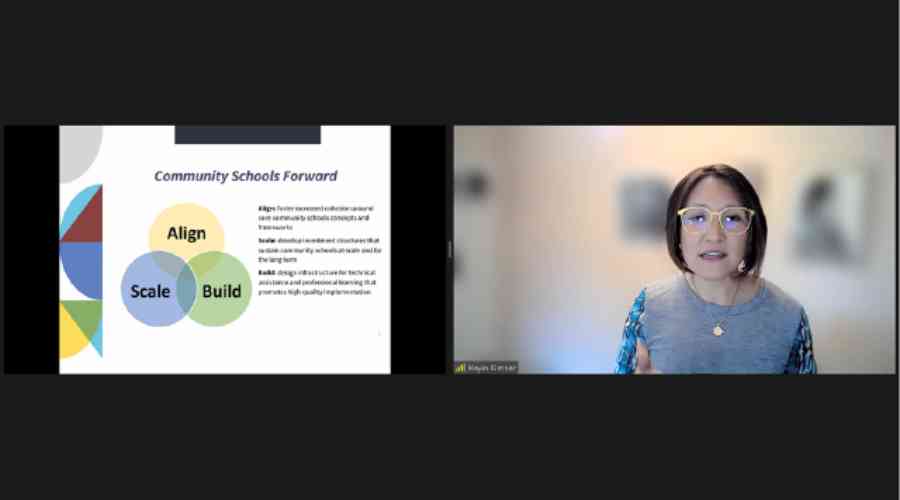

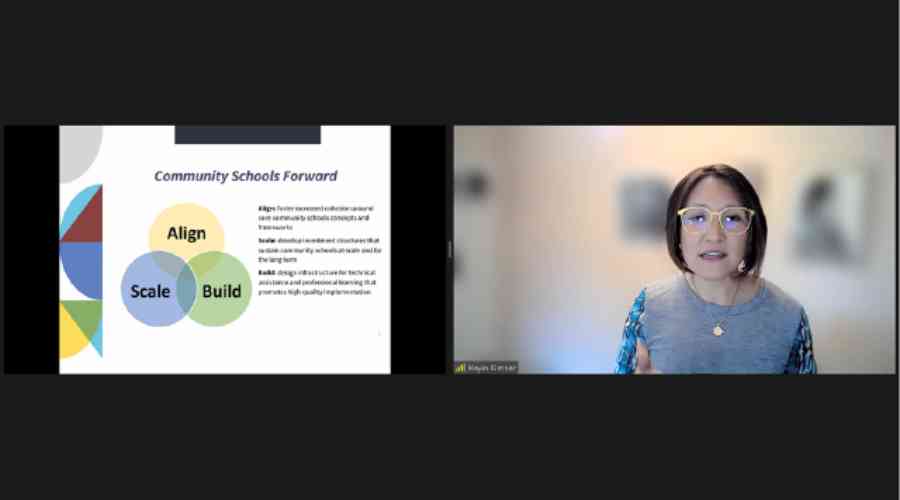

On Friday 3/25, our Managing Director, Hayin Kimner, had the opportunity to provide comments at the White House to share about lessons learned and the role for the federal government and administration in sustaining and expanding community school implementation. Hayin highlighted three areas in which federal policy might play an important role strengthening the field:

1. Alignment: This is about increasing cohesion around core community school concepts; this alignment too must be modeled by and reflected in federal investments. The “systemness” that is central to coherence and alignment of multiple whole-child, whole-family and whole-community strategies is often overlooked in favor of fragmented funding streams and programmatic silos that unintentionally undermine an effective and mutually reinforcing child-serving system. Consider how, for example, separate federal investments in Choice Neighborhoods, Promise Neighborhoods, Community Schools, The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act could better reflect alignment with a coherent and shared set of standards for implementation, outcomes measures, and explicit connections to other federal and state investments. This work starts from the top. Such through lines are invaluable to creating the collective impact needed to realize population level shifts in student and community well being and academic success.

2. Scaling: Funding is an obvious component of scaling sustainable community schools. Many of us are pleased by the recent announcement from Secretaries Cardona and Becerra to provide support to make it easier for schools to access Medicaid funding to provide on-campus health services. It is important to note however, that this work cannot just be about supporting schools to better tap into funding streams. Fundamentally, it should not be the sole responsibility of LEAs and schools to shoulder the responsibility (and staffing) of accessing, braiding and blending funding to pay for the costs of meeting the needs of students. A couple examples:

3. Building: Building successful community schools demands reliable data, rigorous evaluation, and a focus on improvement. Implementation of community schools is developmental and iterative; the goal is systems transformation which cannot be measured solely by tracking transactional program metrics and piecemeal individual outcomes. While evaluation of community schools must happen – it is the only way we can improve and advance as a field – we must build evaluations that appropriately and reliably measure the impact of the full strategy. Evaluation needs to be in service of strengthening practice – not picking winners and losers. Funded evaluations (and their methodologies) from US ED’s Office of Innovation and Research provide useful and relevant examples of rigorous mixed-methods studies that account for complex, developmental implementation of education innovation.

Again, we are so appreciative of the Biden administration's support and recognition that equitable community school success requires a multi-sector, multi-level commitment to change. Another big shout-out to many colleagues and partners who were also part of this important policy-informing conversation!