Cross-District Partnerships for Rural Community Schools

Introducing CS Journeys! In this series, practitioners like you share how they bring various aspects of community schools implementation essentials to life in their unique school communities. Want your own CS Journey chronicled here? Please get in touch.

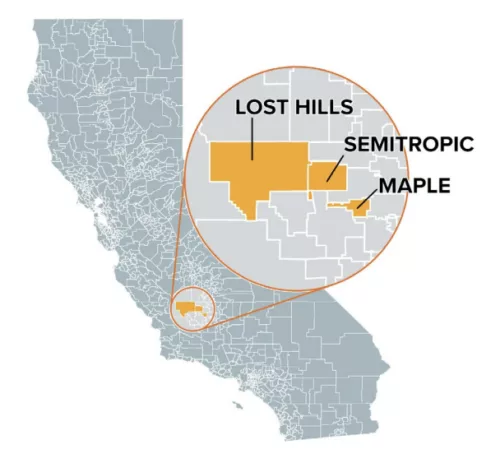

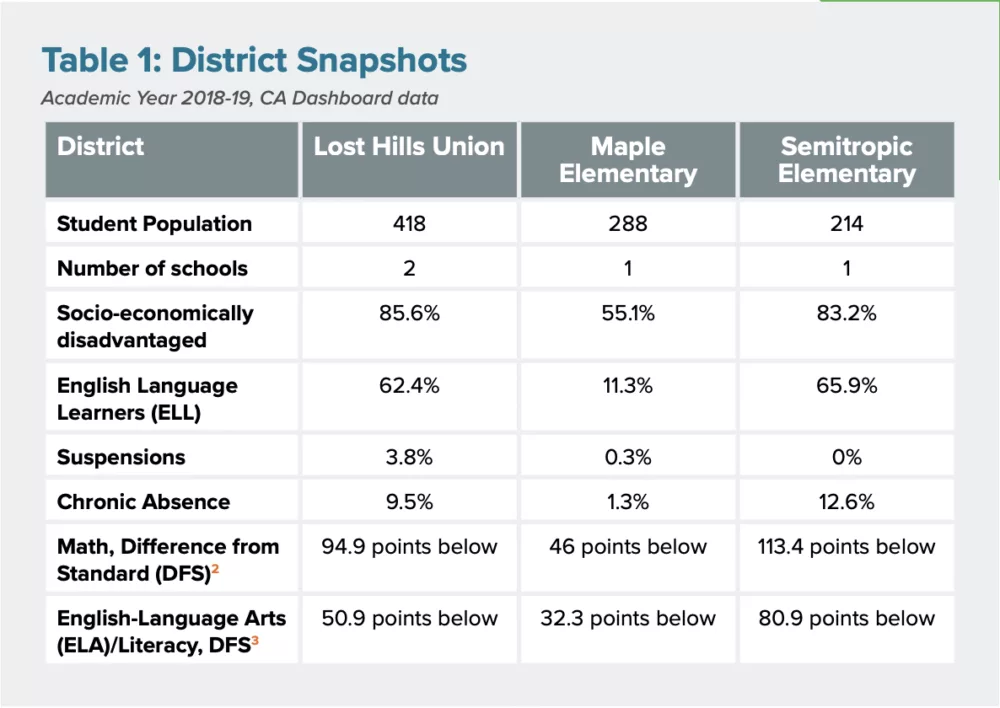

Kern County sits at the southern tip of California’s Central Valley, nestled amongst almond orchards and framed by rolling foothills. The area of West Kern County is primarily an unincorporated, rural, farm and oil community, serving a mix of farmworker and landowner families. The three districts featured in this story – Lost Hills Union Elementary, Semitropic Elementary, and Maple Elementary – serve 920 preschool-8th grade students across 650 square miles. Semitropic and Maple are single-school districts, administered by a Superintendent-Principal; Lost Hills Union includes two schools. In 2018, all three districts were joint recipients of the highly competitive federal Full-Service Community Schools Grant Program.

Since then, the consortium has established the Children’s Cabinet of West Kern County, hired parent liaisons and community school coordinators, created a regional preschool program and Expanded and Summer Learning Program, hired a shared math coach to increase instructional effectiveness, created an attendance campaign to address chronic absence, and secured regional social workers and other mental health resources. In August 2022 – in spite of the vast challenges facing the district and communities because of the Covid-19 pandemic – Lost Hills Union was recognized as among the most improved districts in the state in both English Language Arts (ELA) and Math.

These Kern County districts are pioneering a unique kind of community school partnership in low-resourced, geographically spread out, rural communities: a cross-district community school strategy. District leaders Julie Boesch, Bethany Ferguson, and Fidelina Saso share how they built this work.

Community partnerships are at the core of the community school approach. And in rural communities, the partnerships landscape presents unique challenges. Rural communities seldom have the breadth of service providers available in urban settings; specifically, fewer organizations or entities offering support services. Additionally, rural districts often span vast geographic areas, and partners are not always located within or even nearby the community. Partner organizations, and their service-providing staff, might be based in a relatively nearby urban center – which may still be dozens of miles from schools.

This all has implications for partnerships. Service providers may not necessarily be from or familiar with the community’s context, which can make it take longer to create trusting relationships with students and families. Requirements for on-site service provision may mean lengthy commutes for providers, which can limit the pool of providers willing to service the community. Lastly, rural service providers are more likely to be part of public agencies, such as county health departments. For school districts, engaging with public systems can often be challenging, especially when the district or school’s organizational systems, priorities, and cultures are not aligned to those of partner organizations. Additionally, if service-provider staff are contracted through public agencies (like the County Office of Education, or Health and Human Services), hiring for those positions can be a long administrative process, leaving months of staffing and service gaps. All three Kern County district leaders cited staffing shortages and retention as major challenges in their districts – of both core staff and partners. The staffing issues have implications for current staff capacity, as well as for longer term planning. Saso commented, “It just becomes overwhelming at times. You feel like you're spread too thin.”

At the same time, from these challenges comes innovation, creativity and a “get it done” approach that makes rural communities and their schools well-suited for community schools work. The three leaders point to some of their powerful assets. In small rural communities, educators have often been working together, in different capacities, for years, and therefore, have a certain degree of relational trust – a critical element of sustained community school work. And, in small rural communities where staff often hold multiple roles and there are fewer administrative hurdles than in larger organizations, districts can be more flexible and nimble.

“We don’t have to ask permission from the … facilities [manager] or health department to expand our after hours program. We can decide we’re doing it, and make it happen,” said Boesch.

The cross-district partnership – which now includes six districts, including two high school districts – came together in 2018 when Michael Figureroa, Founder and CEO of Figueroa Consulting, reached out to leaders in Maple Elementary, Lost Hills Union, and Semitropic to gauge their interest in applying for a multi-million dollar federal Full-Service Federal Community Schools grant.

Boesch had known Figueroa from his prior work at the Kern County Superintendent of Schools. Figueroa, raised in the Central Valley, had left California to pursue a doctoral degree in education, and returned to the area in 2015 to continue serving the community. When Figueroa proposed applying for the federal grant, Boesch and the other two leaders jumped at the opportunity. Says Boesch:

“All of us are very much willing to do whatever it takes in order to serve our kids. That's really what our focus is. Whatever that means, we're willing to do that. If it requires some work, we'll do work. If it requires creating a program, we'll create a program. If it requires billing each other and sharing staff and sharing resources, we'll do that because the focus is always on doing whatever we can to get additional resources for our students. That's how it got started.”

Despite each of these educators knowing each other and having some degree of collaboration prior to the FSCS grant, the grant catalyzed a much closer and intentional partnership. District leaders began by identifying the root causes of the challenges all three school communities were experiencing. All three were struggling with student performance in ELA and math, chronic absenteeism, and staff retention. Ultimately, the districts identified five shared priority areas: early childhood education; expanded learning; math instruction; family and community partnerships; and social and health services.

As in communities across the state and the country, the need for mental health services and social-emotional support became even more pronounced during the pandemic. In rural communities, however, affording, hiring, and retaining mental health staff pose unique challenges. These three districts were no exception. “Individually, none of us can afford all the people we need,” said Boesch. So, they got creative.

When Maple’s intern school psychologist mentioned to Boesch that they would be interested in a full-time position after their internship ended, Boesch came up with an unusual idea. Unable to afford a school psychologist solely with funds from her school/district’s general budget, Boesch went to Lost Hills Union and Semitropic with a proposition: sharing the position across their four school sites. Together, the three districts created a customized job description, along with a plan to share the psychologist’s time and salary. The results: “Together, we get one school psych[ologist] that does all the social work, and all of the counseling…as well as special ed[ucation] testing. Alone, we can't have that. We don't have that.” says Boesch.

Sharing mental health staff is not always ideal – in contrast to a full-time equivalent (FTE), site-specific staff person. But small rural districts are used to not letting the perfect get in the way of a reasonable alternative. By collaborating to create a shared job description and role allocation, the three districts were able to attract a high quality candidate for one full time position rather than compete for a much-harder-to-hire part-time position.

Similarly, the three districts struggled with retaining social workers. Most social workers were County Health and Human Services employees, who lived in the nearby city and preferred a job closer to home. The long commute (1-2 hours each way) was a deterrent, so the districts often ended up with a small pool of willing candidates, with service gaps between hires (e.g., a lag between when the former staff left and the new staff person was brought on board). After years of frustrations, the partners again got creative and decided to build their own in-house program: “We came together and we decided, ‘Hey, we can develop our own social worker program. We can develop our own job descriptions. We can hire a lead to oversee [the program]’”, said Saso. In contrast to contracting with the County, the districts were able to better screen candidates and be more hands-on in the hiring process. Additionally, hiring their own social workers in-house has allowed for closer relationships and collaboration between school staff and social workers. The program also created a career pathway for training and hiring local prospective social workers, and a more tenable and long-term solution to ongoing staffing issues.

Each of the districts’ data showed that math was a shared challenge. Says Saso: “Academics is part of our community school model because we're serving the whole child. Our scores showed that’s where we had a need; not only our state assessments, but also our local assessments, and our classroom assessments indicated we had to do something about… our math learning.… When the community school model came along, math became one of our [shared] pipelines across the districts.”

The districts struggled for the first three years to hire somebody to strengthen math instruction (e.g., coaching for math teachers). They ended up each hiring consultants to help each of the districts, with some success. In early 2022, the consortium was able to hire a full-time, shared math coach: a sixth grade classroom teacher at Maple who was strong in math and looking to leave the classroom. The three districts came together and offered the teacher the math coach position. Saso reported:

“We were able to quickly come together and make that happen. [And it was such a win] to keep somebody with that knowledge within our small school districts because generally, we lose those people to bigger school districts. To be able to keep her and have her assist teachers in other school districts was what we needed to do.”

Hiring and building capacity from within has tremendous advantages. Through their prior, ongoing collaborative work, the coach was already familiar with all three districts. The coaching position also allowed Maple to retain a skilled educator. Sharing the position across sites has led to rich sharing of instructional practices and resources. For example, Lost Hills Union had already been holding regular professional development “math talks” with staff; the coach was able to build on that practice, expanding math talks to include Maple teachers in the subsequent year.

Expanding the quality and quantity of time students spend engaged in learning is one of the central tenets of community schools. When the three districts received the federal FSCS grant in 2018, Maple’s campus was in the middle of construction so they were unable to hold summer school that year. Boesch called her colleagues at Semitropic, and asked if they could run Maple’s summer school on their campus. Semitropic agreed. Each District independently contracted with the Boys and Girls Club, and both districts’ bus drivers worked together to coordinate transportation for students. “My bus drivers took my kids to [the Semitropic] bus driver, and their bus driver then took my kids to [the school] site. We all worked together to make that happen,” says Boesch.

The following year (2020), early in the pandemic, summer school was held virtually. In 2021, Maple hosted summer school for both districts on their (newly built) campus. And in 2022, each district had built enough internal capacity to host their own summer program. Growing talent and support from within the community–for example, identifying and leveraging local talent to staff a robust summer program–has been an important facet of the WKC districts’ approach to community school development. In small and rural settings, where staffing can be a limiting factor, community schools can be an avenue to identify and cultivate capacity within the community, reflecting a longstanding ethos of community schools as hubs contributing to neighborhood revitalization and community life.

The districts have recruited staff from other neighboring districts as well. Staff have plans for eventually each district to host its own program. Says Ferguson: “The goal this year is to really take all of our staff, all of her staff, train them all so that they both have a phenomenal experience and are ready to run their own programs next year. Obviously, with a lot of support, potentially still shared resources, whatever we need to do to make it happen for all of our kids.”

Boesch interjected: “It's not that we don't want to work together because we really enjoy serving our kids but we would really love that we would have the opportunity that the kids could attend at their homeschool as well.” As of fall 2022, summer school will continue jointly between Maple Elementary and Semitropic Elementary, whereas daily afterschool programming will be held individually at each site.

Ferguson confirms: “[Semitropic summer staff] have built the relationship with people from Maple. If they need the help, they can easily shoot that email to them and who knows, we might have somebody that roves between the two sites just for the summertime…. I don't see us completely breaking apart in the years to come. I think it's a great opportunity, not only for my staff but her staff as well.”

The work underway in Kern County and the partnership amongst district leadership and team members reflect many promising community school practices, enabling conditions, and capacities, as described in the Community Schools Essentials Framework.

At the core of the collaborative’s work are five common priority areas: early childhood education, expanded learning, math instruction, family and community partnerships, and social and health services. These five priorities drive collaborative decision-making across the partnership; when negotiating action and resources across multiple stakeholders, the shared vision is essential to cohesive action.

Additionally, while each district has their own unique culture and context, they have a common commitment to creatively solving both shared and unique problems in service of students’ success.

Quality relationships are the foundation of all of the districts’ community schools work. One of the advantages of small/rural communities is the fact that oftentimes in small communities, folks know each other through formal and informal networks and relationships. The power of those relationships help district staff to identify opportunities for collaboration.

As their partnership has grown over time, the district leaders have come to lean on each others’ unique strengths and work together to address different needs. “I think that's what makes our team stronger: different personalities, different people have different knowledge in different areas,” remarks Saso. Drawing on Boesch’s prior experience as an expanded learning leader to provide guidance to the cross-district program is one such example.

In working together, the districts have also been creative about helping each district meet their individual needs. When asked what advice she’d offer to those pursuing collective work, Saso urged others to “be ready to do for others,” and to put the needs of partner districts in step with your own.

Over the past five years, the three districts have developed a braided funding strategy that draws from multiple funding streams, including Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) funds, Expanded Learning Opportunity Program (ELO-P), Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER), Student Support and Academic Enrichment Program (SSAE), Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) funding, School Climate Transformation grants, Title I funding, Federal Full-Service Community Schools Grant Program, the California Community Schools Partnership Program (CCSPP) pilot, and the Emerging Bilingual Collaborative. In isolation, the funds that each district receives from each discrete grant still do not cover the resources necessary to best support all of their students. But when district leaders come together and explore ways to braid funding, share resources and apply their strengths to each other’s challenges, funding can go much, much further.

The shared staffing across partnerships is one example of strategic use of resources. Districts usually consider funding strategies that bridge across traditional income sources – general fund, one-time use dollars, philanthropic donations. The West Kern Consortium expands this notion to consider how districts can blend and match funds across partner districts to create a more distributed and sustainable funding strategy that does not rely solely on one district’s revenue.

Without intentional and strategic collaboration, each of the districts individually would not have the resources to accomplish what they have done collectively. Boesch reflects, “It’s not that everybody gets an equal amount but everybody gets what they need the most.” For example, participation in the consortium has benefited Maple students; with a 55% unduplicated student count, Maple often does not qualify (individually) for state funding opportunities that are directed to districts with high percentages of higher need students. But by working together with the other districts and averaging their demographics, Maple both contributes to and benefits from available resources.

All three district leaders agreed that this work would not have succeeded without convening and facilitation support from a strategic partner organization. Since the start of the initiative, Figueroa Consulting has played the role of a backbone partner in the West Kern Consortium's community school development and implementation. Figueroa has been not only grant-writer for the collaborative, but also organizer, facilitator, strategic planner, mediator, and intermediary. Figueroa’s time, expertise, and willingness to roll up his sleeves and work alongside his school-based colleagues were essential, especially in the early years of the initiative as the districts were building their individual and collective community school capacities.

Community school development entails expanding the traditional role of the school by incorporating both more functions and stakeholders into the school’s fabric. A backbone agency can provide critical staffing and guidance to facilitate this work. Additionally, an effective backbone agency will bring an orientation towards data-informed decision-making, continuous improvement, and deep knowledge of the landscape (including and outside of the education sector). This is especially important in terms of the ability to bring new partners to the table to support the community schools effort.

In many successful community schools, backbone support is provided by a local community-based organization. For example, Children’s Aid in New York is a child and family service agency that, in addition to providing discrete services, plays an active, collaborative and advisory role in community school development. In small and rural settings, a large community based organization may not be available, nor qualified, to provide this support. In this case, rural districts may need to be creative in how they apportion and staff the functions of a backbone agency to support community school development.

What are your district or schools’ most pressing priorities? What data do you have that confirms this? Who are they priorities for?

Who in your community do you consider a partner? How are you currently engaging with those partners? What are some ways you could be more strategic and/or collaborative in how you work together?

Who would be an “unexpected” partner in your community? Who else has a stake in students’ success? What are some ways you could begin a conversation with them?

The California Department of Education signaled their recognition of some of the challenges rural districts face by giving priority points to CCSPP applications from rural LEAs. Policy-makers and advocates wishing to support equitable access to community school funding opportunities for small/rural students and school should consider:

While these programs administratively may live in different departments at the state-level, they exist simultaneously for districts. In small/rural districts especially, the administrative burden of managing unaligned programs is disproportionate. It is often the same 1-4 people administering, managing, and sometimes staffing ALL of these programs. Consider developing a state “Whole Child Funding Opportunities” master document, with a description of each program, allowable expenditures, application deadlines, and clear case studies of how specific districts have strategically leveraged funding from multiple streams.

Julie Boesch was the superintendent/principal of Maple Elementary School District before joining the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (CCEE) as Assistant Director, Systems of Support in 2022.

Bethany Ferguson has served as the superintendent/principal of Semitropic Elementary School District since 2015.

Fidelina Saso is the assistant superintendent of Lost Hills Union Elementary School District and the project director for the Full-Service Community Schools grant within the West Kern Consortium.

Kendra Fehrer served as the Director of Research & Organizational Learning at the CA Community Schools Learning Exchange. She is a co-author of this piece.

Sylvie Raymond served as an Undergraduate Intern at the CA Community Schools Learning Exchange. She is a co-author of this piece.

With special thanks and acknowledgement to Michael Figueroa for his review of and contributions to this piece.

Suggested Citation: Fehrer, K., and Raymond, S. (2023). CS Journeys: Cross-District Partnerships for Rural Community Schools. Community Schools Learning Exchange. Oakland, CA.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/.

Please note: CSLX administers regular review of the content and materials we produce. The most current version will always appear at the bottom right corner of the page. Have feedback? We welcome you to share your reaction to this resource at https://cslx.org/contact-us.